There were no blood tests, no diagnostic radiology, no sophisticated diagnostic techniques. So it seemed that syphilis, with its protean symptoms and signs, could have been over-diagnosed in earlier years.Ī distinguished 19th century physician, Sir William Osler, wrote in his Textbook of Medicine: “He who knows syphilis knows all of medicine.” In Osler’s time, diagnosis primarily depended on a good history of symptoms and observed manifestations of the supposed disease process. The spirochete for syphilis was not discovered until 1905, and the blood test not devised until a few years later. I next searched medical literature on the prevalence, incidence and treatment of syphilis in the United Kingdom during the 19th century. I understand that they were eventually archived at the Royal College of Physicians, London. I was not allowed to make photocopies, and so took copious notes. They proved to be a trove of medical information on Lord Randolph Churchill and Buzzard’s other patients. She and Teddy authorized me to review them.

Buzzard’s papers with her in a large trunk. His older sister Margaret, now in a Woodstock nursing home, had Dr. Teddy Farquhar, one of Buzzard’s grandchildren, might know something about his grandfather’s medical papers. Lund said that a Radcliffe colleague, Dr. He was now a surgical consultant at Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford and living in Woodstock, Lord Randolph’s old parliamentary constituency. Bill Lund, who had briefly been my superviser at Middlesex Hospital and Medical School in 1968. Soon after I chatted about my quest with an ear, nose and throat (ENT) surgical consultant, Dr. Thomas Buzzard, the neuro-syphylologist who cared for Randolph alongside the family doctor, Dr. Intrigued, I set about finding what I could from secondary sources, and the medical records of Dr. Harris included the charge in a scurrilous 1922 memoir, My Life & Loves, and somehow it became accepted writ. The rumor, he said, began with a disaffected literary agent, Frank Harris, who nursed a grudge against his Uncle Winston. Churchill was convinced that Lord Randolph never suffered from syphilis. Apparently, during their engagement, they became adept at forging each other’s signature so as to spare the other the task, and in this case neither was aware they were already “signed in.” (Goodness, I wondered, wee all the books purportedly signed by WSC signed by him, or some by his wife? But never mind.) He showed me their visitors book where the signatures of Winston Churchill and Clementine Hozier appeared twice on the same page. Peregrine had virtually all of Lord and Lady Randolph Churchill’s papers and effects, amid much Churchilliana. The visit was fascinating from many perspectives. We met in 1995 at his house in Hampshire. Through Celia Sandys I was introduced to Peregrine Spencer-Churchill, Sir Winston’s nephew. But undue speculation is rightly criticized by medical experts and historians. This is certainly possible with world statesmen, who leave broad records. It is sometimes helpful to consider the subject’s vocational performance.

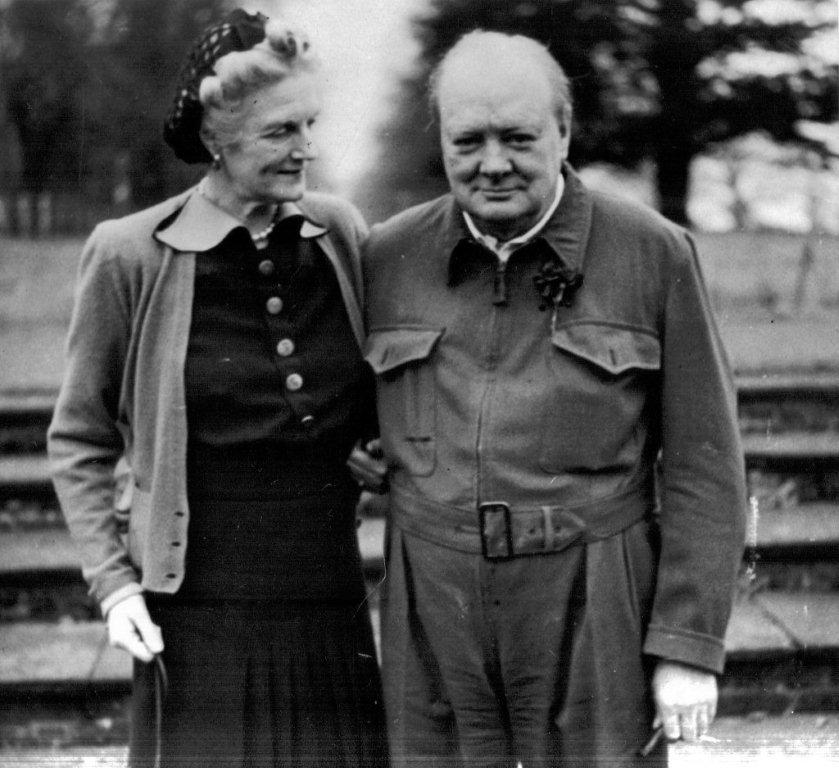

Establishing real evidence is difficult, especially if the subject is long deceased. Thus began my search for the truth about Lord Randolph’s final illness.Ī medical biographer is devoted to matching a medical diagnosis to the signs and symptoms of a medical condition. But not all! Celia Sandys, one of his grand-daughters, immediately challenged me: “Are you quite sure?” Well, no. The story, after all, was accepted by his son Winston, and most of the family. In an innocent remark at a Churchill conference long ago, I repeated the long-running assertion that Sir Winston’s father died of syphilis. Above: “ His slim, boyish figure, his mustache which had an emotion of its own, his round protruding eyes, gave a compound interest to his speeches.” Lord Randolph Churchill in his prime, circa 1885.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)